LOW FEMME

Andi Schwartz

PDF of this Piece // PDF of Issue 7 // Table of Contents

ABSTRACT: In this paper, I explore the connection between affect and femme gender presentation. Femme interventions in queer theory have created a high femme standard which conceptualizes femme as performative and brazen. This impressive legacy has caused anxiety for some femme scholars. Using these femme scholars’ critiques of high femme gender theory and autobiographical experiences, I offer low femme as an alternative femme form that emerges when negative affects interrupt a high femme aesthetic. This essay contemplates low femme as an aesthetic and emotional form alongside Low Femme, five mixed-media images.

Introduction: Femme Failures

What happens when affect disrupts the performance of gender? This essay accompanies a series of mixed media pieces titled Low Femme that offers a new femme aesthetic based on the collision of high femme aesthetics and anxiety. Low Femme explores the effects that feelings like depression and anxiety have on the body, and the impact this has on gender presentation, particularly femme gender presentation. Ann Cvetkovich (2012) asserts that negative affects like depression can be spurred by social and political phenomena. Cvetkovich’s work operates as part of a collective project dubbed Public Feelings that touts campy slogans like: “Depressed? It might be political!” (Cvetkovich 2012, 2). She points to the gay and lesbian political turn to homonormativity and “queer neoliberalisms” as a source of this depression: “the queer activism of the 1990s has had its own share of political disappointments, as radical potential has mutated into assimilationist agenda and left some of us wondering how domestic partner benefits and marriage equality became the movement’s rallying cry” (Cvetkovich 2012, 6). Jose Esteban Muñoz (2006), too, views depression as political. Muñoz understands depression not as universal, but as socially and historically specific (2006, 675); he states there are particularities to “feeling brown” and feeling down (2006). He writes: “Depression is not brown, but there are modalities of depression that seem quite brown” (Muñoz 2006, 680). Here, Muñoz is referring to the “shattered” ego that is a result of attentiveness to the social—a vital aspect of brown politics (2006, 680). Keeping in mind the specificity of negative affects and their link to the political and social, Low Femme considers the anxiety produced by the nagging pressure to achieve or adhere to a high standard of femme style—both physical and emotional—that is commonly found in femme theory.

Femme is a queer feminine identity that stems from working-class lesbian bar culture of the 1940s and 1950s in North America (Nestle 1992). Femme has often been paired with the butch, a masculine-presenting lesbian. During the 1940s and 1950s, the masculine/feminine aesthetics of butch-femme style kept lesbians safe—invisible to the undiscerning, straight eye. Joan Nestle (1992) writes about femmes holding their lesbian communities together in these tough times with their sexuality and emotional labour. She writes: “Femmes poured out more love and wetness on our bar stools and in our homes than women were supposed to have” (Nestle 1992, 138-139). Femmes are routinely sexualized and objectified, and disproportionately expected to perform emotional labour, but these are also highly prized femme skills. However, interpersonal relations are often a source of anxiety for me, which I explore in the fourth image of the Low Femme series. The image is Bach’s Rescue Remedy Spray (used for stress relief) with the text “I heard femmes are supposed to be receptive, but even hugs scare me.”

As butch/femme culture evolved, femme was further theorized as a queer and political gender and sexual identity (Nestle 1992; Hollibaugh 2000; Brushwood Rose and Camilleri 2002). However, when queer theory was introduced to the academy in the late 1990s, its emphasis on subversion and deconstruction seemed to privilege butch, trans-masculine, androgynous, and drag expressions over the seemingly more normative femme expression. This insidious queer narrative holds fast in academia, but also holds sway in queer communities. The fear of not being queer enough is a real one for femmes. The third image in the Low Femme series reflects my own anxiety about being queer enough. The image shows chipped red nail polish on a femme’s fingernails with the text, “I’m not convinced by your topic. It’s more important to be butch.” This was another student’s response to my interest in researching femme identities, revealed in the obligatory round of introductions during my first week of graduate school. I froze—at once a failed queer and a failed academic.

Queer theory and femme theory reveal that femme identity is always already a series of failures and rejections. Femme, in its queerness and excess, fails to be normatively feminine. Femme, in its femininity, fails to be normatively queer. Much of femme theory is about embracing these failures, and actively rejecting the aspects of normative femininity that seek to regulate marginalized subjects and bodies. Lisa Duggan and Kathleen McHugh (1996) write, “The feminine white woman is offered ‘respect’ only in relation to those excluded from the sacred domestic and its ‘protections’—the slave, the mammy, the whore, the jezebel, the wage slave, the servant, the hussy, the dyke, the welfare queen. ‘Femininity’ here is the price paid for a paltry and debasing power” (157). Femme has been an alternative mode of embodying femininity while refusing to cash in the paltry prize of normativity. Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha (formerly Leah Lilith Albrecht-Samarasinha) writes:

Femme is queer. Drop a femme into a straight bridal shower and she’ll stand out as much as a drag queen would. Femme in the working-class, often colored, contexts I have experienced it in is brassy, ballsy, loud, obnoxious. It goes far beyond the standards of whitemiddleclass feminine propriety. Femme women, like MTFs, construct their girl-ness and construct it the way it works for us. At our strongest, we are the opposite of feminine heterosexual women who are oppressed by their gender and held to impossible media standards designed to foster hatred of one’s body. (1997, 142)

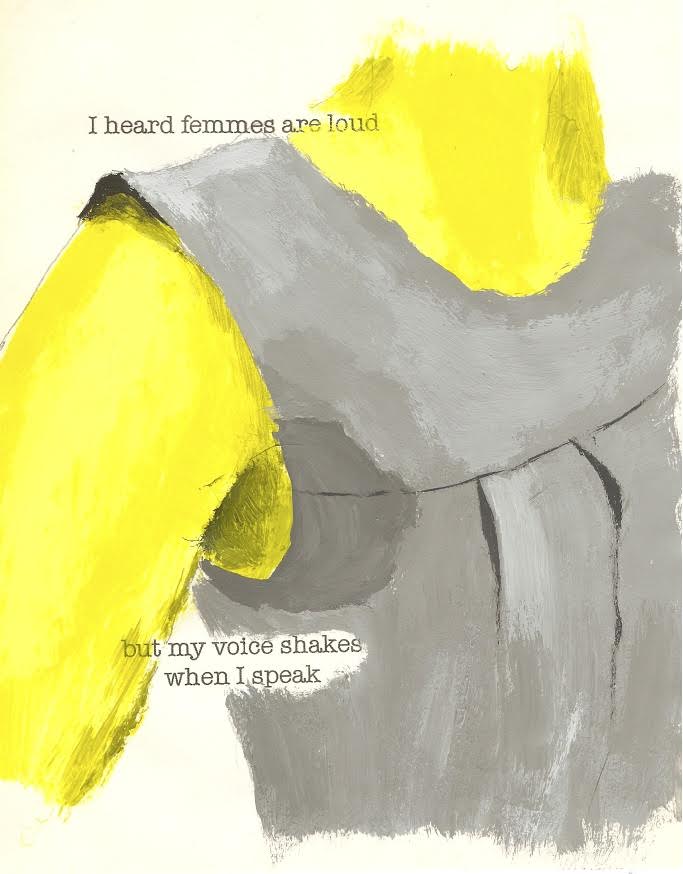

Femme, in many ways, is feminine failure repackaged and reclaimed as a defiant triumph. This has been femme theorists’ response to the treatment of the femme in queer theory: adopting the language of queer theory to argue that femme is a queer, performative, ironic, subversive, and radical identity (Duggan and McHugh 1996; Harris and Crocker 1997; Hollibaugh 2000; Brushwood Rose and Camilleri 2002). The result is a canon of femme theory that centres on a “high femme” aesthetic: a put-on, exaggerated, and performative—even drag—version of femininity that is simultaneously tough, brash, and brazen. Embedded in this aesthetic is another femme expectation that makes me nervous: the second image in the Low Femme series is a femme’s sweat-stained dress paired with the text, “I heard femmes are loud but my voice shakes when I speak.”

Low Femme started with a question: if there is such a thing as high femme, then what is low femme? My answer is informed by personal experiences of falling short, of failing to meet the expectations of femme identity performance as described in the femme theory (both high and low) that I have loved, that has offered me a sense of belonging and community. Heather Love’s work on queer histories provides a framework for understanding the strong attachment to the fore-femmes found within femme theory. She says queers look to the past because “contemporary queer subjects are also isolated, lonely subjects looking for other lonely people, just like them” (Love 2007, 36). Experiencing “backward” or negative affects, like loneliness or isolation, drives us to seek a community and a history by tracing the lineage of our identities that are, in part, characterized by similar affective experiences. Muñoz also argues that the “depressive positionality” offers the potential to know others with whom we share an affective or emotional valence (2006, 682). Love encourages us to see these connections “not as consoling but as shattering” (2007, 45). Indeed, it is shattering to try and to fail at performing an identity that leads to a community that could chase away isolation and loneliness. Love (2007) writes of contemporary queer subjects attempting to “save” the queers of the past through historical projects (51), but turning to queer histories is a way in which we also try to save ourselves; we seek to save ourselves from loneliness, isolation, and sadness by finding ourselves in the images, stories, and identities of the queers of the past. This is certainly what I have done with “femme.” Finding “femme” meant finding myself, it meant seeing myself, and it meant understanding myself. More than that, it meant finding a language and community. In other words, it meant finding a context in which it made sense that I existed. And now to feel as though I am falling short of femme, as though I am failing to be femme, well, this is “botching it” (Love 2007, 51) in a different sense.

Using autobiographical experiences to inform the Low Femme project follows Cvetkovich’s exploration of personal narrative and memoir in An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality and Lesbian Public Cultures (2003) and Depression: A Public Feeling (2012). Although Cvetkovich (2012) acknowledges the critiques of using memoir, especially in academia, she asserts memoir’s usefulness as a methodology and uses personal narrative as a way to reroute around writer’s block and explore new ways of thinking (16, 17, 75, 82). Memoir has been particularly useful for femme theory, as femmes’ life writing is central to this literature and has served as a corrective to the queer narratives that privilege butch and masculine identities (Brightwell 2017). Analyzing trauma in the context of butch-femme sexualities, Cvetkovich says: “Writing about these emotional and sexual intimacies becomes a way of forging a public sphere that can accommodate them” (2003, 82). Similarly, I hope that writing about the intimacies of femme failures forges a place in femme theory that can accommodate them. I hope my public acknowledgement and exploration of femme failures broadens the scope of femme identities and that it introduces a new dialogue or a new direction in which to take femme theory. Aestheticizing the often private and personal feeling of failure is an attempt to undo shame associated with failure, to generate a public dialogue about femme failures, and to reroute my way to/through/around femme. I see this project as a way to generate different versions of femme and foster communities that can hold the history of femme, while also being less afraid to botch it.

High Theory/Low Theory, High Femme/…Low Femme?

In The Queer Art of Failure (2011), Jack Halberstam introduces the concept of low theory, a theory that gives credence to “the in-between spaces” (2), a “theoretical model that flies below the radar, that is assembled from eccentric texts and examples that refuse to confirm the hierarchies of knowing that maintain the high in high theory” (16, emphasis in original). Halberstam’s low theory offers something of a reprieve to my high femme anxiety. The first image in the Low Femme series is a femme’s face wearing sloppy, crooked eyeliner accompanied by the text: “Resist mastery.” Bolstered by Halberstam’s directive, I try my shaky hand at femme performance and, predictably, I botch it.

In Low Femme, I use the concept of “low theory” coupled with an affective “low,” or sense of anxiety, depression, or otherwise negative feelings. I call these feelings “low” because of the low energy and low function that they seem to instill in the body and the psyche. Queer theorists frequently characterize depression as a “low.” Muñoz describes depression as feeling “down” (2006). Cvetkovich writes: “everyday life produces feelings of despair and anxiety, sometimes extreme, sometimes throbbing along at a low level, and hence barely discernible from just the way things are, feelings that get internalized and named, for better or for worse, as depression” (14, emphasis mine). Further, she says: “panic brings you down fast” (Cvetkovich 2012, 63); and anxiety leaves one “unable to get up” (Cvetkovich 2012, 44). Cvetkovich’s also articulates anxiety and depression as “ordinary” feelings (2012, 12), which makes them even more apt terrains on which to play with low theory, as articulated by Halberstam.

My use of the term “low” also comes out of femme scholars’ critiques of femme identity theory and their personal anxieties about meeting the standards of femme gender performativity imposed by said theories. Particularly apt is Robbin VanNewkirk’s (2006) apparent dread of the term “high femme,” which I repeat here:

I resist the label of femme sometimes… This is particularly true when people start talking about high femme; versus what? Thankfully, you don’t hear people talk too much about low femmes, but it still leaves me wondering if I can truly manage this identity… Can I still be subversive if my actions are not always a manipulative and tactical strategy for resistance? What if the subversive potential of femme identity becomes an expectation that I cannot always fulfill? (76-77, emphasis in original)

Lisa Walker (2012) also quotes VanNewkirk’s passage and adds: “it echoes the anxiety of women such as [Jess] Wells and [Amber] Hollibaugh, who find that their age makes them question how they can continue to fulfill the subversive potential of femme in the same fashion they effected as younger women” (807). Walker uses her own experience of ageing as a jumping-off point to question the emphasis on femme drag and femme performativity in the construction of femme identity in femme theory. She writes: “the playground of consumer culture was becoming a minefield: shimmery eye shadows emphasized fine lines; matte red lipstick suddenly looked too brash; vintage clothes looked suspiciously like I might have bought them new” (2012, 796). Like me, Walker (2012) suspects she might be failing as a femme, and will continue to do so if the standards remain the same: “If, as I fear, I am aging out of my own somewhat muted version of alternative femininity, I am probably closer than ever to flunking femme science and embodying a ‘repulsive’ gender style” (798). Here, Walker is responding to Duggan and McHugh’s take on normative femininity: “an historically dated and utterly repulsive gender style” (1996, 156). Duggan and McHugh mock the sincerity of “delicate, morally superior feminine white women” (1996, 157) and question “the dignity and wisdom of anyone who would wear pink without irony, or a floral print without murderous or seditious designs” (1996, 157). Walker further questions her ability to measure up to these femme standards: “Surely, they were speaking metaphorically about not wearing pink and florals? Or maybe I am a failed femme” (2012, 797). The codes of what purportedly constitute femme identity and performance seem to be setting a high standard, so high, in fact, that it causes femmes to experience fear and dread, and to question their own femme identity and the construction of femme identity itself. Anxiety over femme failure seems to be increasingly common which, in keeping with Love’s theory that queers seek “other lonely people, just like them,” is somewhat comforting. In Low Femme, I draw on Walker’s sense of failure as well as my own. The final image in the series is a femme in flat shoes with Walker’s quote “Surely, they were speaking metaphorically about not wearing pink and florals?”

In Low Femme, I juxtapose visual representations of physical experiences of a nervous, anxious body with textual representations of mental and emotional ruminations on anxieties and insecurities related to fulfilling a femme identity. The result is a collection of five images that wryly suggests a new femme aesthetic: low femme. Riffing off Halberstam’s low theory, and Walker’s and VanNewkirk’s anxieties around looking femme enough, low femme emerges as a sweatier, sloppier, quieter, and shakier version of her high femme big sister in flat shoes. Along with lipstick, low femme touts Rescue Remedy. Her nervous hands can never produce unchipped nails, or manage those stubborn greys. She can hardly muster a hug, never mind making it to the book launch, the poetry reading, the queer slow dance… Low femme is low in energy but high in anxiety. The series Low Femme further embodies low theory through the use of a rough, unrefined painting style and “bargain brand” materials. Through my art (and femme) practice, I push myself to “resist mastery”—to botch it—and embrace the result. I hope that using failure and low theory to frame my theory and inform my practice will make this artwork recognizable and relatable to a usually unaddressed femme audience: low femmes.

I say, somewhat tongue-in-cheek, that although Low Femme is a series of mixed media images, it could also be considered an ongoing performance piece. As I have previously stated, I drew on my own feelings of femme failure to inform this project, but I also used my own body to create the images. I photographed various parts of my body that represent the physical effects of negative affects like anxiety that I experience. I photographed these physical effects as they naturally occurred on my body to highlight the everyday, ordinariness of negative feelings, as articulated by Cvetkovich (2012, 12). The effects I chose to photograph—sweat, crooked eyeliner, and chipped nail polish—can be particularly devastating to a femme image, as they suggest a failure of femininity. Other images, like flat shoes and Rescue Remedy, though they may not be considered physical effects of negative affects, also signify failures in femininity and femme identity, which is purportedly sexy, bold, and loud. I then used these photographs as references to paint the images on paper printed with text. The printed text represents anxious thoughts or insecurities that may either cause the physical effects described above or be a result of experiencing them. The combination of text and image represents the connection between affect and bodily experiences, which is also suggested by Cvetkovich (2012): “To describe anxiety as a psychological state or as subject to mental persuasion doesn’t capture it. In my experience, it was a feeling deeply embedded in different parts of my body. Like physical pain, it kept me fixated on the immediate present, unable to think about other things” (35). Low Femme pays attention to the ways negative affects are mental and emotional, but physical as well. The Cvetkovich passage above and the Low Femme images also indicate that depression and anxiety can act as a roadblock for a variety of pursuits, including those related to gender performance.

Even though these images were created using my own experiences and body, and thus reflect a white experience, I resist the concept of “flesh tones” in my art practice by painting with colours not often associated with skin to create the images of femme bodies. Though this is not sufficient to decentre whiteness in this project (as whiteness is signalled by more than skin colour), it is my way of acknowledging that femme is not only a white experience or identity; these experiences and identities can be (and are) claimed by any body. In fact, femme literature presents ample critique of the normative feminine ideal that is defined as white, middle-class, heterosexual, and able-bodied. Queering femininity is the overt project of femme theory, and often this is done in more ways than one. Most femme literature is written from a queer perspective, but heterosexuality is not the only aspect of normative femininity challenged by femme theorists: the writing of Nestle (1987), Hollibaugh (2000), and Piepzna-Samarasinha (2015) emphasizes how their working-class positionality shapes their femme sexuality, style and politics, while Piepzna-Samarasinha also foregrounds racialization and disability in her femme figurations (2015). The ongoing contributions of femmes of colour, femmes with disabilities, working-class femmes, trans, and genderqueer femmes to femme theory (high and low) demonstrates that “femme” takes many intersectional forms.

Failure as an Art, Depression as Creative

Halberstam (2011) encourages us to view failure not as a defeat but rather a source of potential: “The queer art of failure turns on the impossible, the improbable, the unlikely, and the unremarkable. It quietly loses, and in losing it imagines other goals for life, for love, for art, and for being” (88). Halberstam does not intend for failure to be construed as favourable; the optimism they see in failure is not one “that relies on positive thinking as an explanatory engine for social order, nor one that insists upon the bright side at all costs; rather this is a little ray of sunshine that produces shade and light in equal measure and knows that the meaning of one always depends upon the meaning of the other” (5). Similarly, Cvetkovich (2012) insists that depression should not be twisted into a positive experience, but sees it as an opportunity for creation and alternative thinking. In Depression: A Public Feeling, she writes:

It might instead be important to let depression linger, to explore the feelings of remaining or resting in sadness without insisting that it be transformed or reconceived. But through an engagement with depression, this book also finds its way to forms of hope, creativity, and even spirituality that are intimately connected with experiences of despair, hopelessness, and being stuck. (Cvetkovich 2012, 14)

Muñoz, too, sees potential in a political understanding of depression. He writes: “This political recognition contains a reparative impulse that I want to describe as enabling and liberatory, in the same way that an attentiveness to those things mute within us, brought into language and given syntax, can potentially lead to an insistence on change and political transformation” (2006, 687). According to these theorists, in negativity, depression, and failure lies hope, life, and potential. These theories provide a framework for understanding low femme as a new way of relating to femme identity through failure. Instead of being defeated by these failures, we can use them to challenge femme identity to open up, to see if new understandings of femme can be forged through failure. In forging new identities, the potential for the formation of new communities emerges, too.

Taking cues from Halberstam (2011) to “resist mastery” (11) and Love (2007) to “botch it” (51), Low Femme seeks to embrace failure as a method and to reject shame associated with failure. Halberstam says failure can offer rewards: “Perhaps most obviously, failure allows us to escape the punishing norms that discipline behavior and manage human development” (2011, 3). Though Halberstam is writing here in the context of heteronormative and neoliberal logics, we can understand this in the context of gender identities and queer histories, too; low femme can be understood as a rebellion against femme standards codified in femme theory. This is part of the creativity that Cvetkovich (2012) describes as encompassing “different ways of being able to move: to solve problems, have ideas, be joyful about the present, make things. Conceived of in this way, [creativity] is embedded in everyday life, not something that belongs only to artists or to transcendent forms of experience” (21). In this sense, Low Femme is a creative endeavour that finds new ways of relating to low and high femme theory and new ways of being femme.

Conclusion

Low Femme is a mixed media art project that combines Halberstam’s low theory, personal narrative, Walker’s and VanNewkirk’s critiques of high femme aesthetics, and the lived experiences of negative affects. Low Femme acknowledges the importance of femme histories to contemporary femme identities, but also the anxiety left behind by the standards these impressive legacies have instilled. These anxieties—as well as negative affects that arise from other sources —have physical effects on the body that can interrupt the performance of the particular version of femme outlined in femme theory. To counteract the high femme standard, Low Femme plays on low theory and emotional lows to suggest ways of embracing failure to navigate our way around norms and ideologies that we cannot live up to or compete with. Low Femme finds that embracing failure can be a fruitful way to develop new identities—and, potentially, new communities—while reevaluating the ways we relate to negative affects. Cvetkovich, Halberstam, Muñoz, and the Low Femme project demonstrate that failure, depression, and anxiety need not necessarily be fixed or avoided or be considered unproductive, but should rather be considered alternative routes that undercut standards of success and happiness we never agreed to.

Using personal experiences of anxiety and femme failure, I take up these issues in Low Femme, trying, also, to see the humour in it all. Bumbling my way through femme performativity can be crushing: the frazzled hair that will not coif, the sweat stains that ruin dresses, the liquid lines that remain shaky no matter how many fresh starts are made. But sometimes seeing how pitifully you fail can lead to useful challenges and productive critiques of the ideologies you didn’t realize were crushing you. Halberstam, Muñoz, and Cvetkovich provide the framework that allows Low Femme to provoke critiques of femininity and femme identity by allowing the space to engage with experiences of anxiety, depression and femme failure.

Works Cited

Albrecht-Samarasinha, Leah Lilith. “On Being A Bisexual Femme.” In Femme: Feminists, Lesbians, Bad Girls, edited by Laura Harris and Elizabeth Crocker, 138-144. New York: Routledge, 1997.

Brightwell, Laura. “‘I’m Always Not Quite the Femme I Would Like to Be’: The Archive of Femme Failure and Its Implications for Queer Theory Today.” Paper presented at the Annual Congress of the Humanities and Social Sciences, Toronto, ON, May 27-June 2, 2017.

Brushwood Rose, Chloe and Anna Camilleri, eds. Brazen Femme: Queering Femininity. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2002.

Cvetkovich, Ann. Depression: A Public Feeling. Durham: Duke University Press, 2012.

———. An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures. Durham: Duke University Press, 2003.

Duggan, Lisa and Kathleen McHugh. “A Fem(me)inist Manifesto.” Women and Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 8, no. 2 (1996): 153-159. doi: 10.1080/07407709608571236

Halberstam, J. The Queer Art of Failure. Durham: Duke University Press, 2011.

Harris, Laura and Elizabeth Crocker, eds. Femme: Feminists, Lesbians, and Bad Girls. New York: Routledge, 1997.

Hollibaugh, Amber. My Dangerous Desires: A Queer Girl Dreaming Her Way Home. Durham: Duke University Press, 2000.

Love, Heather. Feeling Backward: Loss and Politics of Queer History. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007.

Muñoz, Jose Esteban. “Feeling Brown, Feeling Down: Latina Affect, the Performativity of Race, and the Depressive Position.” Signs 31, no. 3 (2006): 675-688.

Nestle, Joan. A Restricted Country. Ann Arbor: Firebrand Books, 1987.

———. The Persistent Desire: A Butch-Femme Reader. Boston: Alyson Publications, 1992.

Piepzna-Samarasinha, Leah Lakshmi. Dirty River: A Queer Femme of Color Dreaming Her Way Home. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2015.

VanNewkirk, Robbin. “‘Gee, I Didn’t Get That Vibe from You’: Articulating My Own Version of a Femme Lesbian Existence.” Journal of Lesbian Studies 10, no. 1-2 (2006): 73-85.

Walker, Lisa. “The Future of Femme: Notes on femininity, Aging and Gender Theory.” Sexualities 15, no. 7 (2012): 795-814.

Andi Schwartz is a Ph.D. candidate in Gender, Feminist, and Women’s Studies at York University. She works at the intersection of critical femininities and digital culture. Her research interests include femme identities and communities, online subcultures and counterpublics, and radical softness. Her writing has been published in GUTS, Broken Pencil, Herizons, Shameless, Daily Xtra, and Ada: A Journal of Gender, New Media, and Technology.