THE RIGHT TO REMAIN: READING AND RESISTING DISPOSSESSION IN VANCOUVER’S DOWNTOWN EASTSIDE WITH PARTICIPATORY ART-MAKING

Aaron Franks, Andy Mori, Ali Lohan, Jeff Masuda, and the Right to Remain Community Fair Team

All photographs by Trevor Wideman

PDF of this Piece // PDF of Issue 4

ABSTRACT: The Right to Remain Community Fair Team are coordinator Ali Lohan and community peer arts facilitators Quin Martins, Andy Mori, Herb Varley, and Karen Ward. The RRCF is the arts phase of the three-year “Revitalizing Japantown?: A unifying exploration of Human Rights, Branding and Place in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside” community research project, in partnership with Gallery Gachet, the Greater Vancouver Japanese Canadian Citizen’s Association, the Nikkei National Museum and Cultural Centre, PACE, the Potluck Café Society, the Powell Street Festival Society, the Strathcona Business Improvement Association, and the Vancouver Japanese Language School and Japanese Hall.

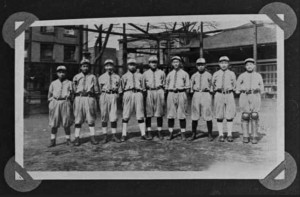

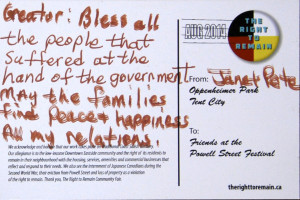

Front of Postcards: (1) from Powell Street Festival goers to the Oppenheimer Park Tent City campers: Asahi Men’s Baseball Team, Paueru gai, Vancouver; (2) from Oppenheimer Park Tent City campers to the Powell Street Festival goers: Tent City, Oppenheimer Park, Vancouver, August, 2014.

Powell Street Festival/Oppenheimer Park Tent City Postcard Project, August 2014

Reflection, in response to Nishant // 15 November, 2014

Dear Nishant,

Thank you for your interest in the Right to Remain Community Fair (the RRCF) currently taking place in Occupied Coast Salish Territories. We are glad you enjoyed our work at the Powell Street Festival in August (http://www.powellstreetfestival.com). As neighbourhood artists with the RRCF we are contributing to the research project “Revitalizing Japantown?” (www.revitalizingjapantown.com) through a peer-led series of participatory arts workshops for and by DTES residents and allies. One element is that labeling neighbourhoods can be a way of gentrifying them. Maybe there is a need for “counterlabels”? Maybe, if marketable new “lifestyle” names like “JapaGasRailtown” (http://twitter.com/cuchilloyvr) are commodifying the culture and class of the people who built the area, we need to counter with names that represent and respect the lives of those who have been and are still being pushed out?

“Japantown” refers to an old portion of the Vancouver Downtown Eastside neighbourhood around Powell Street that was allocated for Japanese migrants to Canada (Nikkei) beginning in 1877. Its residents were evacuated shortly after Pearl Harbor in light of the wartime paranoia and racism that became institutionalized at all levels of government (Adachi, 1976). So in my mind the revitalization of “Japantown” could only really mean a reinstatement of its residents and heritage there, but the issue is more complicated than that. Is it in the interest of some to gloss over history? The Nikkei obviously weren’t the first to be violently displaced out of the area. The DTES was one the earliest places of Indigenous settlement in what became Vancouver.

An Indigenous RRCF community artist has said that through his time dealing with the development of the area he came to realize that there had been a whole series of displacements from this patch of land. The first one chronologically was the regional Indigenous peoples, then the internment of Japanese immigrants, then the black residents displaced by freeway viaducts around Hogan’s Alley (see http://www.blackstrathcona.com), and presently those of low income and marginalized residents who have no property ownership (Blomley, 2004). Each time this has happened it has violated residents’ “Right to Remain” in what one local “Revitalizing Japantown?” participant says “has always been a poor person’s neighbourhood.”

The links between this series of displacements struck us again during the RRCF when the Oppenheimer Park Tent City sprung up to highlight both the plight of the homeless and the Supreme Court decision on native land rights. This coincided with the Powell Street Festival, an annual street festival that reclaims for the August long weekend this area of Japantown to celebrate its culture and Nikkei culture generally. The festival organizers showed respect for the occupation of the park that they would normally use for the event by relocating to nearby streets and sidewalks, showing solidarity in the struggle for the Right to Remain.

In a “Revitalizing Japantown?” arts team brainstorming session for the Powell Street Festival we hit upon an idea. Why not have the festival participants write postcards of encouragement to the Oppenheimer Park Tent City and vice versa? This would bridge communities across the divides of history by showing common concern for the Right to Remain. Human Rights should not be abstract gifts from the powerful—the Right to Remain is the right to self-identified homes, identities, ways of making a living, and tools for resisting colonialism and gentrification linked by racist economic exploitation.

I did the graphic design of the postcards, choosing images from the men’s Asahi Baseball team, a legendary local Japanese Canadian baseball program before the war. A second set of postcards designed with a photo of the Tent City occupying the very area of the baseball diamond where the men once stood was also made, to lend a bridge across time in the same location.

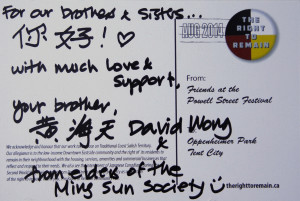

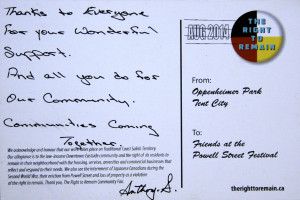

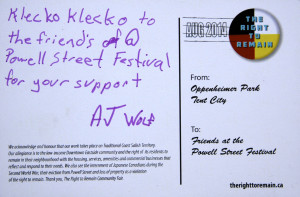

Once implemented at the Festival, over 30 postcards were written and signed by festivalgoers, assisted and encouraged by myself and RRCF arts team members Ali Lohan and Quin Martins. Using a rapidly obsolete medium reinforced the performative aspect of replicating historic communication practices. Arts team members Herb Varley and Karen Ward had the task of taking the Tent City postcards to Oppenheimer Park for its occupants to sign and send back to the festival. There were formalities, obstacles and issues of trust in order to get those postcards signed and sent back, but it was still being carried on well after the PSF ended.

I feel the postcard project to be a great success as a living history “lesson” in the personal craft of handwritten cards of solidarity turned into group petitioning and in the acknowledgement of Human Rights, all touched on at once. It also reminded us all of how the Powell Street Festival was originally born of a call for activism and Japanese Canadian redress, and that historic apologies still hang in the air waiting to be said, with their attendant responsibilities.

– Andy Mori, artist

Works Cited

Adachi, K. The Enemy That Never Was. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart Limited, 1976. Blomley, N. Unsettling the City: Urban Land and the Politics of Property. New York: Routledge, 2004.

Postcards from Powell Street Festival to the Oppenheimer Park Camp. Top to Bottom: postcard from Paola; postcard from Lane; postcard from David; postcard from Pia.

Postcards from the Oppenheimer Park Camp to the Powell Street Festival. Top to Bottom: postcard from Anthony; postcard from AJ; postcard from Janet; postcard from Janet.

The Right to Remain Community Fair: Participatory Art as Research in The Downtown Eastside

“Revitalizing Japantown?: A unifying exploration of Human Rights, Branding and Place in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside” (www.revitalizingjapantown.ca) is a three-year community research project funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada that links the current rapid gentrification via capitalist accumulation in the Downtown Eastside of Vancouver to prior colonial appropriations from First Nations, Japanese, other racialized residents, as well mental-health system survivors and low-income people.

From June 2014 through January 2015, we are working with Gallery Gachet (http://gachet.org), the Nikkei National Museum and Cultural Centre (NNM) (http://centre.nikkeiplace.org) and six other partners to engage low-income residents in a Right to Remain Community Fair (RRCF) in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. The Fair features monthly Human Rights Arts Workshops and presentations at valued DTES spaces like the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users (VANDU), Aboriginal Front Door (AFD), the Interurban Gallery, and the Carnegie Community Centre. In March-April 2015 and October 2015-January 2016, Gachet and the NNM will host separate exhibits inspired by these workshops, their participants, and their arts process.

Art can celebrate and gather people (and gather people in celebration); it can also accuse and scream. Both and all variations in between are possible. In this spirit the Fair hasn’t looked to make “good,” celebratory, or educational art about Human Rights. We have worked with partners and residents to develop the Fair because the ethic of relationship-building behind participatory art as research stands in opposition to the current development model in the area, which has roots in the neighbourhood’s colonial history. This is a development model in which:

[T]he Low Income community in particular, which is overrepresented by its racialized communities, indigenous, and particular migrant communities, is at a disadvantage as the area becomes reconceptualized as an “artist district” without an analysis of class. (Gachet staff member, interview, 2014)

Art is an exchange of experience, not just economy.

It’s often said that the DTES has the highest concentration of artists in Vancouver, and quite possibly Canada. The observation can serve many agendas and has been repeated so often that it might be cliché. It’s not a precise equivalent, but “highest concentration of artists in Vancouver” can have the same lazy effect as “poorest postal code in Canada,” as generic celebrations of “concentrated artists” (just add water…) smother the neighbourhood with profit-ready notions of “edgy” and “vibrant.”

The City of Vancouver’s recent Local Area Planning Process (LAPP) report (City of Vancouver, 2014) devotes a Chapter (14) to Arts and Culture. The Chapter opens by presenting “art and culture” in the DTES as a thing that comes into being through three areas of increased investment and capacity: Improved Arts and Culture Facilities; Art in Public Places; and Increased Opportunities for the Creative Economy (p.143). In a planning document it’s not surprising that art is (re)placed into the community in this way, as Facility, Place, and (Creative) Economy. Even though it may not be a building or coordinate on a map as in a “Facility” or “Public Place,” the “Creative Economy” is no less specific in how it locates art in the DTES.

While it shouldn’t surprise us, it’s nevertheless important to remember that handling art this way mediates our encounters with the artist’s affective labour and, more importantly for the political economy of the DTES, mediates artists’ relationship with the place they call home. Rather than more opportunities for art-making for artists who live in the DTES, the “spatial fix” creates more opportunities for investment in art as an engine for gentrification in the DTES. All artists have a right to be paid for their craft and to sell their work and skills if they choose. When it comes to clichés the stale romance of the starving artist has had a longer shelf life than most. But it is very doubtful that “increasing opportunities for the Creative Economy” means improved resources (never mind sales) for the many practicing artists of long standing who live in the DTES yet reap no benefits from gentrification.

Art to repossess the DTES (and its image)

Elsewhere in the LAPP document, the city refers to strategies to “accelerate vibrancy” (see the section on “Built Form,” p.70). But people and places aren’t simple particles that on e can slow down and speed up. A strategy of “accelerating vibrancy” to “increase opportunities for the Creative Economy” (p.143) plays out as an accumulation strategy that rubs out the concrete complexity of life—the complexity of meeting needs, of what change is—through the abstract space of development. Living, changing, and meeting needs while under the threat of dispossession and marginalization demands an art that exchanges more than just money.

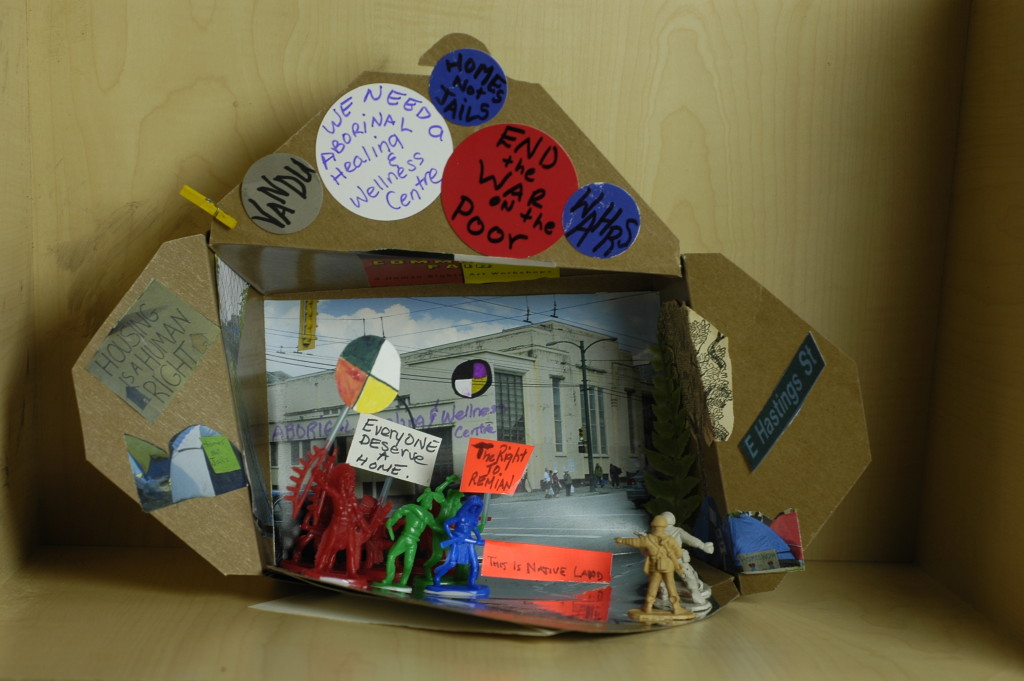

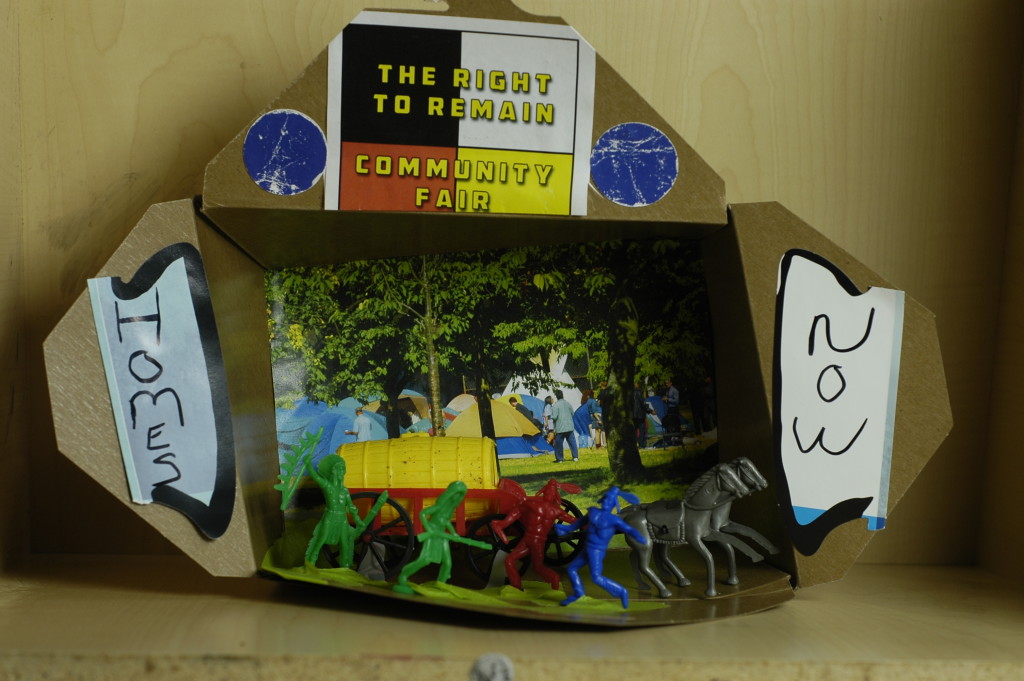

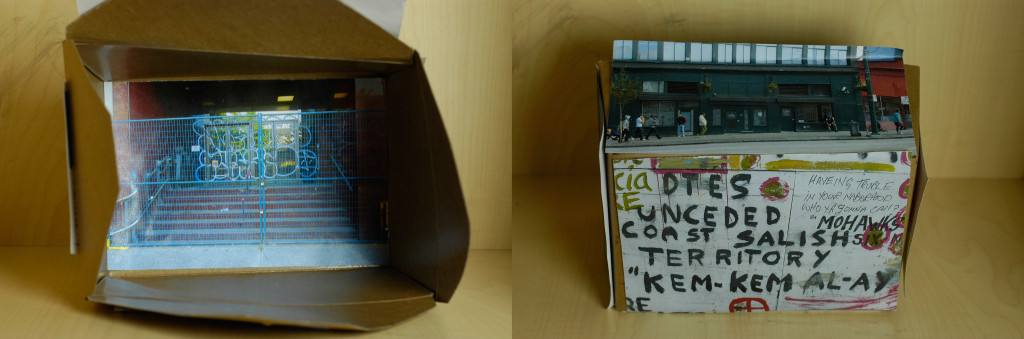

The individual and collaborative artworks emergent out of the RRCF embody this, as does Andy’s personal description of the creative postcard exchange between homeless campers “occupying” Oppenheimer Park (unceded Aboriginal territory) with their tents and longhouse and members of the Nikkei diaspora attending the Powell Street Festival. And while many of the works created during the RRCF (e.g., the dioramas below) contain direct messages of resistance, there is more to their aesthetic than polemic, or ‘giving voice’:

[I]n terms of the trauma and suffering which is part of—in especially the low-income communities, marginalized, displaced communities—everyday experience…one of the differences…is thinking through these elements as an element of quality, not an element of marginalization. (Gachet staff member, interview 2014)

The motto of Gallery Gachet, a Community Partner for the Fair, is “Art is a Means for Survival.” The Right to Remain Community Fair approaches art as a means for shared debate, healing, pleasure and pain, and an understanding of what it has meant and means to survive in the DTES in the past, present, and future, using the tools of Human Rights and art-making. The “Revitalizing Japantown?” team of researchers, students, residents, and community organizations are privileged to work in a community where art, creativity, and the complexity of living are considered basic parts of knowing, history, and politics, rather than frills and add-ons.

– Aaron Franks, “Revitalizing Japantown?” research team member

Works Cited

City of Vancouver. Downtown Eastside Plan. 2015. URL http://vancouver.ca/files/cov/downtown-eastside-plan.pdf (last accessed 27 April, 2015).

Dioramas – (workshop at VANDU, facilitated by Karen Ward and the RRCF Team)

“Homeland Security” – Herb Varley

”Aboriginal Healing and Wellness Centre” – Tracey Morrison

“Homes Now” – DJ Joe

No Title – Doronn Dalzell

The Right to Remain Community Fair (RRCF) was a year long community art-as-research component of the SSHRC-funded community research partnership “Revitalizing ‘Japantown’?: a unifying exploration of Human Rights, branding and place in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside”. The RRCF Team is Ali Lohan, Quin Martins, Andy Mori, Herb Varley, Karen Ward and Trevor Wideman. Aaron Franks was RJ-RRCF project Coordinator and is a postdoctoral researcher in Cultural Studies at Queen’s University, Canada; Jeff Masuda is project Director and Canada Research Chair (Tier II) in Environmental Health Equity in the School of Kinesiology and Health Studies (Queen’s).