UNCANNY EROTICS: ON HANS BELLMER’S SOUVENIRS OF THE DOLL

Jeremy Bell

PDF of this Piece // PDF of Issue 2

Next PieceABSTRACT: The German-born Surrealist artist and writer Hans Bellmer is currently most famous for the two dolls he created in Berlin during the 1930s, alongside accompanying photographs and texts. Controversial for the challenging and oftentimes sexually graphic character of his work, Bellmer has often been criticized by feminist thinkers. Beginning with the recently hosted Double Sexus exhibition in Berlin, where his work was presented alongside that of Louise Bourgeois, and then examining his doll photographs and other works, I argue that—far from reifying gender norms—Bellmer deconstructs the stability of the male ego.

Double Sexus

Hans Bellmer is not for everyone. His work makes some people feel uncomfortable—squeamish even. Actually, his work makes a lot of people feel uncomfortable. An encounter with Bellmer’s work might be like discovering our parents’ collection of illicit images (whether a fading set of polaroids, or a series of bookmarks saved on a laptop) were it not for the fact that, with Bellmer, that discovery is accompanied by a realization of just how much more prurient our parents’ tastes are than our own. Despite this provocative character, however, Bellmer remains one of the most compelling and controversial artists of the 20th century. If anything, his significance is “repressed” alongside the desires for violence and (de)sacralization that creep into everyone’s fantasies once in a while. Clearly, Bellmer takes such fantasies seriously. Modernism’s reputation for cruelty is already well established, but with Bellmer it is especially transparent. This is what gives his work its frightening or “uncanny” character. As a virtuoso of BDSM and “perverse” sexualities, the upsetting character of Bellmer’s work has not diluted a great deal since his lifetime. Its provocative character persists past the work of many of his fellow Surrealists whose “tenant of total revolt” (Breton 125) seems to have been digested culturally and appropriated economically, if not by Surrealism’s formal end in 1969 then at least within the omnivorous logic of late capitalist society. Without doubt, this is why many feminists continue to critique Bellmer, whom they often see as misogynistic and/or reifying phallic norms.

Double Sexus, is an exhibition that brings together the work of Hans Bellmer with that of Louise Bourgeois. It was the first special exhibit hosted by the Collection Scharf-Gerstenberg since its founding in 2008 and was hosted from April to August of 2010, before moving to the Gemeentemuseum in the Hague and the Whitechapel Gallery in London. Udo Kittelmann, director of the National Gallery in Berlin, observes, in his forward to Hans Bellmer, Louise Bourgeois: Double Sexus,that the Collection Scharf-Gerstenberg has aimed since its origins to present “an intimate and highly differentiated view of Surrealism and its predecessors and successors” (13). The Collection Scharf-Gerstenberg “is a reticent, introverted collection that speaks to us solely through the aesthetic qualities of its works, without the need [for] verbose explanation.” Hans Bellmer, one of the more prominent representatives featured in the collection, is exemplary. A German exile working in a predominantly French milieu, Bellmer expresses the differentiated view of Surrealism towards which the Collection aspires as well as its aesthetics of introversion and intimacy. As Kittelmann writes: “His small-format photographs, as much as his filigree graphic works created at the drawing-board, require an attentive, meticulous viewer who is prepared to study every detail they contain” (13).

Bellmer is most famous for the doll he began making in Berlin in 1933, and the two cycles of photographs of the posed doll, which were taken between 1933 and 1939. But these souvenirs of the doll,this doll-theme, was only the beginning of a prolific, forty-year career in which he produced not just photographs, but also etchings and writings. His 1954 text, Little Anatomy of the Physical Unconscious or the Anatomy of the Image, for example, will extend the doll into a more general theory of the body, and into what Bellmer himself calls “the physical unconscious.”

In order to give a clear and precise picture of this we will say: the body is comparable to a sentence that invites you to disarticulate it, for the purpose of recombining its actual contents through a series of endless anagrams. (Bellmer 36)

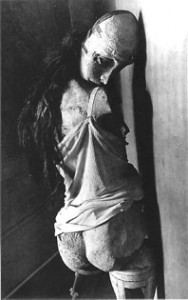

This is what Bellmer does mercilessly: following construction is de-construction and dis-articulation, all “for the purposes of recombining its actual contents” into endless carnal rearrangements. Bellmer’s work touches on fetishism, sadomasochism, and scopophilia, among other themes. “Bellmer is not so much a prophet of desire as one of obsession…with sex, especially with the unrealized, and largely unrealizable, imaginative implications of sex. His obsession has gone such lengths that it concentrates on the impossible, because only the impossible, it seems, could hope to satisfy it” (Peppiatt 26). In this sense, Bellmer’s significance extends beyond what we might rather diminutively call “erotic art.” The fact that the Marquis de Sade and Georges Bataille both had a great influence on Bellmer’s entire corpus is a testament to the contradictory forces of desire and lust as well as shame and aversion. An image from his second cycle of photographs is representative of these themes (see Figure 1). At once infantile and tumescent, its face is covered by its breast-like ball joints, and its eroticism is only emphasized by the chair-back, the blonde wig, and the ribbon. Brought together with its naked, mechanical parts, we see a body that, despite proper appendages, possesses two clearly articulated pelvises. It is disturbing, but far from conclusive. Like Bellmer’s work in general—his little girls, toys, and dolls are penetrated, decaying, or dissecting themselves like a nightmare or a repressed reminiscence of childhood—he clearly expresses the darker, more frightening side of Surrealism.

Figure 1: Hans Bellmer – “Untitled” from Games of the Doll, 1935

Placing Bellmer alongside Louise Bourgeois, then, is instructive. These two artists not only share motifs in common—of the doll and the “hermaphrodite,” of auxiliary torsos and limbs—but they also share themes such as the body’s fragmentation, vulnerability, or rebellion. Kyllikki Zacharias, curator of the Collection Scharf-Gerstenberg, notes that the commonalities between Bellmer and Bourgeois are not entirely accidental. The two share curiously similar biographies, with both spending most of their lives estranged from their homelands—Bourgeois moved from France to the U.S. in 1938, while Bellmer permanently left Germany for France in 1939. Further, both saw their repudiation by their fathers as a site of struggle in their work. Bellmer and Bourgeois both draw us back into a world of childish and polymorphous perversity. They resist not just the will of their own particular fathers but, as Zacharias puts it, “the system of the father” as well. Zacharias writes: “Erotic themes and physical, sexual forms are almost predestined for a rebellion against the father figure, and taboos can be marvellously breached with sexual hybrids” (29). We can compare this sentiment to what Alyce Mahon, in her more general studies of Surrealism, has noted; that is, that from the 1930s onward, Surrealism came to embody a “politics of Eros” (9-21).

The Double Sexus exhibit was thematized around Bataille’s L’histoire de l’oeil (1928) and Diana of Ephesus, and accompanied by selections from Henry Miller’s Sexus (1949) and an unpublished text by Elfriede Jelinek, “Body and Woman (Claudia).” Taken together, it is evident that this “politics of Eros” is openly cultivated by the Collection. In her “Greeting” to the exhibit, Christina Weiss thanks Udo Kittelmann and Killikki Zacharias for providing support that “places a particular—erotic—emphasis within the ‘Surrealist world’” (Kittlelman et al. 23). From the scopophilic precision of Bellmer to the amorphous, maternal sensuality of Bourgeois, and from the confrontational Jelinek to Miller’s more hilarious scatology, this acute eroticism is challenging. It raises not only art-historical questions about Surrealism, its context and its heritage, but it also raises more personal questions. How are we to respond to this clearly troubled imagery? For example, consider Bourgeois’s 2005 sculpture Femme, which depicts a cloth head and torso with two breast-like forms on a pillow under a glass bowl. This figure is typical of her work. Without appendages, the figure cannot escape; further, its simple open eyes and mouth suggest a scream, but we do not hear it beneath the glass. As with Bellmer’s doll, there is definitely something scary about whatever is happening.

The influence of Bataille on both Bourgeois and Bellmer is clear. It is visible in Bourgeois’ La maladie de l’amour (# 2, #3) (2008), which is a series of phallic drawings with tiny blue eyes gazing from their tips that recall the blue eyes of the priest at the climax of L’histoire de l’œil (whom the protagonists rape, murder, and enucleate). But, with Bellmer, the influence is even more direct. Bellmer met Bataille in 1945 through the publisher Alain Gheerbrant, who asked Bellmer to illustrate a new edition of L’histoire de l’oeil. Bataille’s influence on Bellmer is seen in the drawings, etchings, and photographs emerging from these studies, as well as in those Bellmer would later create for Madame Edwarda. “I agree with Georges Bataille,” Bellmer later explains, “that eroticism relates to a knowledge of evil and the inevitability of death[;] it is not simply an expression of joyful passion” (qtd. in Webb 369). But the vision is clearly reciprocal: Bataille’s conception of Eros, of a sexuality that is always already tainted by sin and the consciousness of death and that is only possible accompanying the death or absence of God, finds few better visual correlates than in Bellmer. “In essence,” Bataille writes in Eroticism (1957), “the domain of eroticism is the domain of violence, of violation” (16). And violation is what we have with Bellmer: it is visible in the “suppressed girlish thoughts” that he hides in the unfinished panorama of the first doll’s belly, but also in his final series of etchings, Petit traité de morale (1968), which concern the mysteries of the Catholic confessional as well as Sade. Like with Bourgeois, but especially with Elfriede Jelinek, the controversial Nobel-prizing-winning author who directly addresses the battle of the sexes and the exploitation of feminine sexualities, Bellmer too seems to be exploiting feminine sexuality. However, in this way, he appears to be more like Miller, in that this exploitation is very masculine and heterosexually oriented. It seems unsurprising, then, that the doll and his other work is made by a man. Sixty years later, Cindy Sherman’s sex dolls, which are directly inspired by Bellmer and by Robert Gober’s extraneous body parts (which themselves are indirectly inspired by Bellmer), offer much more ambivalent sexualities by comparison. This ambivalence is so even if the themes of perversion and blasphemy, if not the cruelty in Bellmer, are hardly reiterating of the status quo.

So, we might ask: is the primary difference between Bellmer and Bourgeois sexual difference? By difference, I mean not just an opposition between the sexes, but also a difference oriented around the enigmatic forms that such an opposition compels: the phallus, the vulva, the androgyne, and so on? Indeed, sexual difference, for both Bellmer and Bourgeois, seems to present a problem, a source of tension that differentiates them from one another, and a persisting site of inquiry in their work. As the curators of Double Sexus acknowledge, Bellmer and Bourgeois are both deeply preoccupied with these distinctions, even as they also aim to overcome them. Calling into question simpler anatomical distinctions and also the social hierarchies these distinctions embody, their work culminates in the sexual hybrid. For even as they acknowledge these distinctions, they thus aim to cross the divide that separates them, from the masculine to the feminine and vice versa, from phantasy to fear and back again. All of this is visible in the palpable eroticism of Bellmer and Bourgeois.

A tangible eroticism is only part of what makes the Double Sexus exhibit so interesting. For even if Bellmer and Bourgeois both challenge our notions of identity and the binaries between self and other, masculine and feminine, and the beautiful and the grotesque, the question remains: does Bellmer reiterate the force of the “male gaze” or disrupt it? Bellmer’s “Souvenirs of the Doll” Bellmer’s introductory essay to Die Puppe is a good starting place in response to this question, as it helps to illustrate some of the correlations between perversion, fetishism, and the polymorphous body in his work, as well as their bearing on the visual plane more generally.[1]

Souvenirs Relative to the Doll: Variations on an Articulated Minor

Fit joint to joint, testing the ball-joints by turning them on their maximum position in a childish pose; gingerly follow the hollows, sampling the pleasure of the curves, losing oneself in the clamshell of the ear, creating beauty and also distributing the salt of deformation a bit vengefully. Furthermore, don’t stop short of the interior; lay bare suppressed girlish thoughts, so that the ground on which they stand is revealed, ideally through the navel, visible as a colourful panorama electrically illuminated deep in the stomach. Should not that be the solution? – Hans Bellmer, “Souvenirs Relative to the Doll”

Restricted, since all that can be said about her bound, the limit. In the most space of the narrowest view, one seeks by calculating, while quibbling, in place of her heart, one evaluates faith in childhood. – Paul Eluard, Games of the Doll

What are these souvenirs relative to the doll? Put simply, they are the two cycles of photographs Bellmer took of the dolls between 1933 and 1939, alongside his accompanying writings. Primarily consisting of close-ups, the first cycle of doll photographs largely outline its construction. In one photograph, the doll’s various parts are laid out in a birds-eye view (see Figure 2). A vertical leg enframes its horizontal torso, hands, feet, face, two glass eyes, and some feathers; dissembled and carefully arranged, it gives us a radically disarticulated tableau with no suggestion of life. In another image, the doll stands in a kind of portrait (see Figure 3). Viewed from behind and pressed close against a wall, the doll wears a long black wig and a white chemise. The chemise is lifted teasingly. Demurely, the doll looks back over its shoulder, as if playing a coy game. The position of the doll’s “gaze” stands out against its vacant, mask-like expression, with emptiness in place of eyes, and the rough, unfinished character of the plaster complexion. Here, shy playfulness couples with ruin: at once the object of desire, the doll is also without life, the fetish. The doll’s ambiguous status as medium cannot be overlooked here. It stands ambivalently between photograph, sculpture, and text. The rumpled bed-sheets and lace, the hula hoop and the marble, the chair-back and the long-stemmed rose together with a high-heeled shoe, all initiate the unfolding of a strange story about the doll’s assemblage and destruction—a kind of photographic journal, if you will, of perversion, sexual difference and their hauntingly displaced narratives.

Figures 2 & 3: Hans Bellmer – “Untitled” from The Doll, 1934

“What am I looking at?” This is only one of the many questions that the doll begs of its viewer. With a skeleton consisting of broom-handles and metal rods, a hand and two feet of carved wood, a plaster torso and head with supplementary wigs, shoes and stockings, as well as additional clothing and other props, it feels wrong to even see the doll as a singular or unified body. In fact, there were two dolls. Of the first, which he worked on from 1933 to 1934 Bellmer took approximately 30 photographs. Fourteen of these were printed alongside “Souvenirs Relative to the Doll” in 1934 as Die Puppe or The Doll, a small, privately published book. Following his contact with the Surrealists, all of these photographs would be reprinted along with four previously unpublished others in a two-page spread of the following, sixth edition of Minotaure under the heading “Doll: Variations on the Assemblage of an Articulated Minor.” The seventh issue of Minotaure printed more photographs of the doll, this time illustrating the prose poem “Appliquée” by Paul Eluard, which was inspired by the doll. Later, in June 1936, Die Puppe was translated into French by Robert Valançay as La Poupée. This is when Bellmer began constructing his second, more complex doll. Formed around a dynamic central ball joint, he took more than one hundred photographs of this doll between 1935 and 1939, fifteen of which would eventually accompany fourteen poems by Eluard as well as Bellmer’s own “Notes on the Subject of the Ball Joint” as Les Jeux de la poupée or Games of the Doll. Although complete by 1939 (and largely in consequence of World War II), Games of the Doll was not published until November of 1949.

That the head, hands, and legs of the first doll were used in the second doll, but that Bellmer created auxiliary legs and arms, torsos, pelvises and breasts suggest a naivety in enumerating these dolls as unified bodies. In fact, they are more akin to what Freud describes as the child in its polymorphous perversity, or the fragmented channels of pleasure that are unarticulated, neither one nor multiple. If anything, the doll attests to an array of corporeal realities. Like the autoerotic thumb-sucking of the child that moves into genital rubbing and urination, the doll too—like the child “under the influence of seduction” as Freud puts it in his Three Essays on Sexuality—“can be tempted into all kinds of possible transgression” (Freud 167). Bellmer is the doll’s seducer.

“Souvenirs Relative to the Doll” gives us Bellmer’s methodology of sorts, at least at this early stage. Drawing analogies between “little girls” and other items from his childhood, he notes that “certain things in the realm of little girls have always been desired” (Bellmer “The Doll Theme” 171). He notes the delicate and in some ways unattainable character of these items: “They might often be those fragile things, like black Easter eggs decorated with doves and rings of pink sugar that, besides being tempting, luckily possessed no other advantage” (171). In this sense, the souvenirs are quite self-consciously fetishistic, at least psychoanalytically. As Bellmer writes, “people like me only admit with reluctance that it is those things about which we know nothing that lodge themselves all too firmly in the memory” (172). And what “object” lodges itself in the memory further than the maternal phallus? For, as Freud writes in “Fetishism,” “a fetish is a substitute for the woman’s (mother’s) phallus, which the little boy once believed in and which—for reasons well known to us—he does not want to give up” (96). Such well-known reasons, we recall, are the traumas of sexual development, the coming-to-consciousness of sexual difference, and especially the “castration complex.” As Freud writes of the fetishist, “he both retains this belief [in the mother’s phallus] and renounces it; in the conflict between the force of the unwelcome perception and the intensity of his aversion to it, a compromise is reached such as is possible only under the laws of unconscious thought, the primary processes” (96). The fetish then is the compromise; wavering ambivalently between phantasy and reality, it acts as a substitute for the mother’s phallus that allows it to remain present but in its absence.

Characterized as much through its over determination as it is through its empty, lifeless centre, or as much by its lack-of-being [manque-à-être] as its focus as a site of fixation, Bellmer’s souvenirs of the doll are quite comparable to the maternal phallus. Their respective ambivalences cannot be overlooked. With these souvenirs being at once photographs, sculptures, and texts, as well as sexual objects and signs, they are what give the doll its uncanny character where it shifts between a feminine personality and something inanimate. With Bellmer drawing from the same sources Freud used to elaborate the uncanny in his 1919 essay “The Uncanny”—that of dolls and marionettes in German romantic literature and culture—Freud and Bellmer are thus contiguous. As Rosalind Krauss writes of Bellmer’s doll photographs: “This entire series, an endless acting-out of the process of construction and dismemberment—or perhaps the more exact characterization would be construction as dismemberment—could not be more effectively glossed than by Freud’s analysis of [E.T.A. Hoffmann’s novella] ‘The Sandman’” (86). For, as Freud shows us as well, there are valuable connections to be drawn between the somatic and semantic aspects of the uncanny. Etymologically, das Unheimlich (the German word for the uncanny) bears a structural relationship to its proper linguistic antonym, das Heimlich, which translates as “the familiar” but also “the secretive.” The uncanny will concern “something that has been repressed and now returns” (Freud 147). Or as this revelatory citation by Friedrich Schelling puts it, “uncanny is what one calls everything that was meant to remain secret and hidden and has come into the open” (qtd. in Freud 132). Freud illustrates this idea through an analysis of Hoffmann’s novella about Nathaniel, who slips into madness via the return of his childhood traumas but also because of his irrational love affair with Olympia, the life-sized doll that he accidentally mistakes for a real person. Freud hardly considers this part of the story, seeming to “repress” the uncanny effects of Olympia. Enchanted by Olympia, Nathaniel spies voyeuristically on her. When he comes to ask her hand in marriage, Nathaniel accidentally witnesses a fight between Professor Spalinzini, Olympia’s creator, and Coppola (over the ownership of her eyes). Only then does he recognize his error (and even still, he jumps to his death at the end of the story). The anxious doubt that Freud describes is the same anxiety that Bellmer’s souvenirs evoke.

There is an origin myth to the doll. In Bellmer’s own account, its inspiration occurred in 1931, accompanying three relatively synchronous events. First, he received a box from his mother filled with broken dolls, linocut magazines, glass marbles, disguises, and other items left over from his childhood. Around this same time, his family moved from Karlsruhe to Berlin. Bellmer is again put in contact with his young cousin, Ursula Naguschewski, who has been the object of his erotic longings since their youth together. With her again close by, but now as an independent young woman, Bellmer begins revisiting his youthful fantasies. But it is not until 1932—when Bellmer sees Max Reinhardt’s opera production of The Tales of Hoffmann—does his real inspiration for the doll occur. Specifically, Bellmer later recounts, he watched with fascination and horror at the end of Act I when Olympia is torn limb from limb (Webb and Short 20-22).

One sees the influence of this scene on another image from The Doll, where the doll is photographed from a bird’s-eye view on a striped mattress (see Figure 4). It lays disassembled. Her head rests beside her torso, detached appendages, a glass eye, and a brown wig. Carefully arranged, the slightly diagonal lines of the sheet behind the doll, and its bald head only accentuate the texture of the doll’s belly and bald pubic area. Moving back and forth between fetish, seductress, and victim, the doll here evokes a complex dynamic in it is viewer parallel to this, one that fluctuates between fascination, revulsion, and anxiety. This is likely why Hal Foster, in Compulsive Beauty, adopts the Marcusian language of “desublimation” to address Bellmer; in the doll’s complicated conjunctions of castrative and fetishistic forms, Foster sees an untying of repressed infantile drives. “More starkly than any other Surrealist,” Foster explains, “Bellmer illuminates the tension between binding and shattering as well as the oscillation between sadism and masochism so characteristic of Surrealism” (107).

Figure 4: Hans Bellmer – “Untitled” from The Doll, 1934

In fact, Bellmer’s use of the uncanny or unheimliche amidst the other Surrealists should itself not be taken for granted. In 1925, while Surrealism was still in its immediate ascendant, Bellmer made his first trip to Paris. At that time, he had yet to familiarize himself with Breton or the other Surrealists. Only after his publication in Minotaure did Bellmer return; this is when he met Breton and others. But, as Robert Short speculates, the proliferation of automatons and mannequins throughout this period of Surrealism, just after the Surrealists’ contact with Bellmer, suggests his influence. Noting in particular the International Surrealist Exhibition of 1938, where Bellmer’s photographs of the doll were displayed alongside mannequins dressed by Max Ernst, Joan Miró, Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp, Salvador Dalí, André Masson and others, Short calls Bellmer’s doll “the archetypal Surrealist object” (35).

An ostensibly innocent toy had been snatched from the hallowed, protected domain of the nursery, enlarged to child-size, and converted into a garish fetish that arouses the most ambiguous, unavowable and palpably erotic desire. No Surrealist object is more pregnant with riddles – not just the riddles posed by Hoffmann about the natural and the artificial or the living and the dead, but fresh Bellmerian riddles about the states of childhood and womanhood between which the Doll is indeterminably suspended. Bellmer conveyed both the precocious sexuality of the child, already amply documented by Freud, and the residue of childhood imagination and longings in the adult. (Webb and Short 35)

But the influence was clearly reciprocal. Not long after his return to Berlin, Bellmer began his second doll. More complex than its predecessor, it was motivated in part by the enthusiastic reception of his work by the other Surrealists. At this time, Bellmer begins moving the doll from the relatively limited confines of his apartment into the nearby woods, the stairwell, the cellar, the haystack, and so on. This is also the time when he begins doubling the pelvises, and photographing the doll with two pairs of legs, each emerging from either ends of its torso. “The game belongs to the category ‘experimental poetry’,” he writes in his introduction to the second cycle of doll photographs. “If one remembers essentially the game’s method of provocation, the toy will present itself in the form of a provocative object” (Bellmer “The Ball Joint” 212). Taking up even more aggressively the themes of perversion and scandal that are left only implicit in the first doll cycle, the Surrealist notion of the provocative toy as experimental poetry only expands Bellmer’s repertoire.

Such is the scandalof the doll, which is all the more scandalous for echoing what Rosalind Krauss sees as the scandal of Surrealist photography in general, that is, the scandalous “fetishization of reality” that admits of no opposition between the “natural” and the “contrived” (Krauss “Corpus Delicti” 69). For, as Krauss explains, the fetishism of not just Bellmer but Surrealist photography in general is prefaced on a denial of “the natural,” denial also grounded in sexual difference. She argues that “if fetishism is this substitute of the unnatural for the natural, its logic turns on the refusal to accept sexual difference” (Krauss “Corpus Delicti” 71). Such is the fabricated character of reality for Surrealist photography, according to Krauss. But the denial is hardly uniform. As Hal Foster observes, sometimes within Surrealism—as with Bellmer—there is a compounding of castrative and fetishistic forms. At other times, though, the castrative forms are repressed. As he writes: “In this regard the dolls may go beyond (or is it inside?) sadistic mastery to the point where the masculine subject confronts its greatest fear: its own fragmentation, disintegration, and dissolution” (Foster “Amor Fou” 94). In this light, for Foster, what is most perverse and sadistic about Bellmer is precisely what aligns him with the feminine and the fluid and, consequently, against “the phallic order.”

Sexuality is a Machine-Gunneress in a State of Grace

Outlining what he sees as the physiological dimensions of desire and eroticism in his 1954 text, Little Anatomy of the Physical Unconscious, or Anatomy of the Image,Bellmer revisits Freud’s observations regarding the displacements and condensations between language and material reality. In this work, Bellmer attends to the transpositions, exchangeability, and reversibility between them. Starting from the point of a toothache and the movement of its pain into the contraction of the hand and fingers, Bellmer sees this migration of a virtual centre of excitation again in Lombroso’s case of a teenage girl who, with the onset of puberty and accompanying attacks of hysteria and somnambulism, lost vision in both eyes but could see through her nose and left earlobe. He also sees it in another girl who hysterically displaced projections of her sexual organ onto her eye, ear, and nose. More than simply synaesthesia for Bellmer, these experiences illustrate “a bizarre fusion of the ‘real’ and the ‘virtual,’ of the ‘permissible’ and the ‘forbidden,’ which allows the components of one to actually gain in a vague fashion what the other surrenders” (Bellmer Little Anatomy, 8). Here is where he makes the fetishistic aspect of his project most transparent.

It is certain that up to the present time no one has seriously questioned to what extent the image of the desired woman is pre-determined by the image of the man who desires her. This process finally goes through a series of phallus projections that proceed gradually from a detail of the woman toward the whole, in such a way that the woman’s finger, hand, arm, or leg becomes the man’s sexual organ. Thereby the man’s sexual organ could be the woman’s leg clad in tight hose beneath the swelling of the thigh, or a pair of oval-shaped buttocks that emphasize the slightly arched spinal column (Bellmer Little Anatomy,25).

There are a number of parallels between Bellmer and Jacques Lacan, especially in “The Signification of the Phallus.” For, as Lacan puts it in his own terminology, “the phallus is a signifier, a signifier whose function, in the intra-subjective economy of analysis, may lift the veil from the function it served in the mysteries. For it is the signifier that is destined to designate meaning effects as a whole, insofar as the signifier conditions them by its presence as signifier” (579). Just because Bellmer does not adopt the Saussurean language of “signification” should not stop us from seeing analogies. One must wonder about the roles of metonymy and metaphor for Bellmer’s body-as-anagram. The parallels between Bellmer and Lacan are not wholly accidental, either. With both publishing their early work in Albert Skira’s journal Minotaure, the interest that Bellmer and Lacan share regarding the interrelationships between language and the erogenous body were likely the basis of their friendship, even as it also reflects the broader questions of their day. Short’s comments about the 1954 reception of Bellmer’s Little Anatomy by his colleagues are again telling.

Breton himself, despite his perennial reservations on the subject of Bellmer, hurried to send his congratulations by pneumatique. The psychiatrist Jacques Lacan was enthusiastic, and Bellmer’s old acquaintance, Dr. [Gaston] Ferdière signified his approbation with the succinct, “It’s correct.” May Ray gave the book its most appropriate welcome, sending Bellmer the anagram: “Image-Magie” (Webb and Short 121).

Insofar as it coincides with emerging forms of Surrealist eroticism, Bellmer’s work rests at a critical juncture between transgression, representation, and the human body. Of the 1959 International Surrealist Exhibition dedicated to not just Eros, but especially its darker, more Sadean element, Mahon writes, “here, pride of place was given to Hans Bellmer’s Doll, which was suspended from the ceiling like a Sadean victim, her body manipulated and contorted to appear as a double-legged creature, the monstrosity of her form only offset by two pairs of girlish shoes and socks and the vacant stare of her face” (159). This configuration is presented alongside Canadian Surrealist Mimi Parent’s Masculine-Feminine, a “tie made with female hair [ties] the collar of a white shirt and lapel of a black suit”: a photo of Masculine-Feminine is used in the exhibition’s invitation. As Mahon observes, “the hair was sexually suggestive, but also macabre, hinting at a scalp or trophy of some sort” (152). If the fetishism is not explicit in these works, it is still surely deliberate—deliberate and prefaced on a (albeit perhaps sometimes unconscious) disavowal of sexual difference.

Is Bellmer entirely within the phallic register, or not? It is a question to be asked of the interwar avant-garde more generally, that is, of Dada and Surrealism, or of its literary forerunners such as Sade, Baudelaire, and Lautréamont. With Bellmer, because of the persistence and gravity of his erotic obsessions, it is particularly incisive. We might even see this as the stakes of his work, or his wager of sorts, not just on the value of perversion, but also on the weight that such a value carries. “I wanted to help people lose their complexes,” he later explains, “to come to terms with their instincts as I was trying to do. I suppose I wanted people really to experience their bodies—I think this is possible only through sex” (qtd. in Webb 370). In turn, it is unsurprising that Bellmer’s work is so challenging.

The challenging aspect of Bellmer’s work is why critics like Krauss and Foster argue that “a view of Surrealism as simply misogynist or antifeminist is mistaken” (Krauss 17). In Bachelors, her study of nine women artists that addresses Bellmer alongside Claude Cahun, Dora Maar, and other female artists, Krauss explains, in commenting on Dora Maar’s 1936 silver-print photographs of two women’s legs, that, “the categorical blurring in an otherwise perfectly focused image produces a slippage in gender that ends by figuring forth that image of the body-in-alteration that is projected by the phallic woman” (19). Recalling the mother praying mantis as well here—which is also but a mere a pair of legs, Krauss notes—she explains how, as with Bellmer, the castrative and fetishistic elements of these particular photographs are made most plain. Against an overly reductive reading of Surrealism then, she suggests that, far from reifying patriarchal norms along with Maar and other examples of Surrealist photography, Bellmer’s doll photographs express a deep-seated ambivalence, one that, like Sade before them, deconstructs the stability of the male ego. Indeed for Krauss, Foster, and others, Bellmer’s “body-in-alteration” is a direct attack on the seeming coherence of fascist subjectivity.

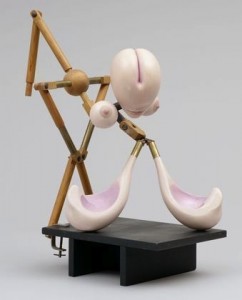

One of the earliest and most insightful of Bellmer’s feminist critics is Xavière Gauthier. She argues that “Bellmer’s Greedy Little Girls are auto-sodomized with great shows of pleasure and pain,” and acerbically observes that, “the doll, which is traditionally given to little girls to help them prepare for their roles as mothers, is sadistically shredded and cut into pieces, then thrown into a provocative pose” (25-26). But she only critiques Bellmer insofar as she critiques Surrealism in general. Both beginning and ending her critical study with Bellmer, she uses his 1937 construction Machine-Gunneress in a State of Grace to typify the Surrealist attitude toward sex in general. The Machine-Gunneress is composed of changeable parts and a cleft through its eyeless head, and machine-like and quasi-human forms combine into a three-foot-high sculpture that at once recalls a naked feminine form, a machine, and a praying mantis (see Figure 5). Gauthier writes that “surrealism attempted to introduce this machinegun into the heart of the bourgeois world and to keep it constantly pointed there for twenty years” (23). For the Surrealists, she explains, sexuality and eroticism are not just aims in themselves, but the clear weapons of choice in the assault on bourgeois society. The subversive power the Surrealists see in Eros, combined with the primacy of overturning sexual values above all else, is what best differentiates it from the revolutionary project of Marxism, with which it otherwise shared much in common (Gauthier 36-38).

Figure 5: Hans Bellmer – Machine-Gunneress in a State of Grace, 1937

Such for Gauthier is part of Surrealism’s hope: “perversion and its rapport with the destruction of society” (48). With its best poetic allegory in Lautréamont’s Chants de Maldoror, specifically when Maldoror makes “a pact with Prostitution to sow disorder in families” (36), this investment in the destructive powers of Eros moves through symbolism into various aspects of the 20th century avant-garde, but it is particularly evident in Surrealism. Finding its origins in Sade, the notion of “perversion and its rapport with the destruction of society” outlines if not a tradition then a hope that finds its strongest deconstructive potential in the systemization of Sade’s thought in the work of Bataille, Pierre Klossowski, and others. Considering Klossowski and Bataille’s respective readings of Sade, the eschatological force of perversion denies of any possible human essence or ground for social order outside of God. Gilles Deleuze, Michel Foucault, and others further elaborate this position (pointedly Nietzschean) after the war. For Klossowski, what the “integral monstrosity” in Sade accomplishes specifically is the collapsing of gender into a singular and perverse polymorphousness. He writes:

The integral monstrosity conceived by Sade has as its immediate effect the working of an exchange of the specific qualities of the sexes. The result is not just a simple symmetrical reversal of the schema of the differentiation within each of the two sexes, with active and passive pederasty on the one side, lesbianism and tribadism on the other. In integral monstrosity as a didactic project for sensuous polymorphousness, the two representatives of the species, male and female, will in their relationship with one another face a twofold model. Each of the two sexes interiorizes this twofold model not only because of the ambivalence proper to each but also because of the embellishment Sade puts on this ambivalence. (Klossowski 35)

Such is as plain in Bellmer for Gauthier as it is in Sade. “With Bellmer, like with Sade, one’s own body is lost,” she writes, “wound into the other, leading to a sort of androgyne (such as Sade’s Juliette)” (Gauthier 57). Remaining sceptical, and preferring, it seems, that each sex maintain itself in an opposition to the other, Gauthier’s remarks nevertheless highlight how even for their critics the sadistic violence of Bellmer and Sade problematizes a simple opposition of the sexes.

Consequently, if Bellmer’s work does rest in an entirely phallic register, it is both self-consciously and self-critically. The body-as-anagram is surely expressive of this, if nothing else: an erotic project, no doubt at once onanistic and oneiric, but a project that is neither oblivious to gender norms, nor an advocate in their favour. If, as Lacan suggests, the phallus is the signifier “destined to designate meaning effects as a whole” (579), what Bellmer’s body-as-anagram suggests in contradistinction to this are “meaning effects” outside this phallic register. For if through repression and prohibition, sublimation and perversion, desire and the pleasure principle move through the body, condensing and superimposing itself in language and consciousness, it is in the body, that enigma of sexual difference, where these “meaning effects” occur, where the phallus is challenged most directly. That is what Bellmer shows us in his in his image of the phallus emerging from inside of the vulva, as portrayed in Little Anatomy. As he writes: “Once I find myself benumbed beneath the pleated skirt of all your fingers and weary from undoing the garlands with which you have encircled the somnolence of your unborn fruit, then you will breathe me into your fragrance and your fever, so that in full light my sex will emerge out of yours” (Bellmer Little Anatomy, 43-44). Of course, there is a kind of violence here. To condemn or dismiss Bellmer on the basis of this violence, however, is to trivialize and ignore a remarkable artist, challenging and tragic to be sure, but one who challenges gender norms as surely as he is reifying them. The feelings Bellmer’s work evoke for us must be differentiated from the strength with which we feel them; the power of these works to touch us is alone a testament to their significance, not to their meaninglessness. To be clear: sexuality is dangerous. It is a site of difficulty that operates at the origins of not just the psyche’s “health,” but also its “pathology.” Bellmer helps us to address this danger. As he would have us realize, sexuality is a Machine-Gunneress in a state of grace: You don’t just fuck with her! Like the mother mantis after copulation, she will consume you!

Figure 6: Hans Bellmer – Miss Eagle, 1968

Notes

1. Where Therese Lichtenstein translates Bellmer’s introductory essay to Die Puppe as “Memories of the Doll Theme” I translate it “Souvenirs of the Doll.” In French it is «Souvenirs relatifs à la poupée». I remain indebted to Lichtenstein’s translation of the document. Except for the title, I here use Lichtenstein’s translation of the text, “Memories of the Doll Theme.”

Works Cited

Bataille, Georges. Eroticism. Trans. Mary Dalwood. 1986. London: Penguin Books, 2001. Print.

Bellmer, Hans. Little Anatomy of the Unconscious, or The Anatomy of the Image. Trans. Jon Graham. Dominion, VT: Dominion Publishing, 2004. Print.

—. “Memories of the Doll Theme.” Trans. Peter Chametzky, Susan Felleman and Jochen Schindler in Therese Lichtenstein. Behind Closed Doors: The Art of Hans Bellmer. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001. 169-174. Print.

—. “Notes on the Subject of the Ball Joint” in Sue Taylor. Hans Bellmer: The Anatomy of Anxiety. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2000. 212-218. Print.

Breton, André. “Second Manifesto of Surrealism.” Manifestos of Surrealism. Trans. Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1969. 117-194. Print.

Foster, Hal. “Armor Fou.” October. 56. High/Low: Art and Mass Culture. Spring, 1991: 64-97. Print.

—. Compulsive Beauty. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1993. Print.

Freud, Sigmund. “Fetishism.” The Unconscious. Trans. Graham Frankland. London: Penguin, 2005. 93-100. Print.

—. “Three Essays on Sexual Theory.” The Psychology of Love. Trans. Shaun Whiteside. London: Penguin, 2006. 111-220. Print.

—. “The Uncanny.” The Uncanny. Trans. David McLintock. London: Penguin, 2003. 121-162. Print.

Gauthier, Xavière. Surréalisme et sexualité. Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 1971. Print.

Kittelmann, Udo, and Kyllikki Zacharias, Eds. Hans Bellmer – Louise Bourgeois: Double Sexus. Berlin: Sammlung Scharf-Gerstenberg, 2010. Print.

Klossowski, Pierre. Sade My Neighbour. Trans. Alphonso Lingis. Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 1991. Print.

Krauss, Rosalind. Bachelors. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999. Print.

—. “Corpus Delecti.” October. 33. Summer, 1985: 31-72. Print.

Lacan, Jacques. “The Signification of the Phallus.” Écrits. Trans. Bruce Fink. W. W. New York: Norton & Company, 2006. Print.

Lautréamont, Comte de. Maldoror and Poems. Trans. Paul Knight. London: Penguin Books, 1978. Print.

Mahon, Alyce. Surrealism and the Politics of Eros, 1938-1968. London: Thames & Hudson. 2005. Print.

Peppiatt, Michael. “Balthus, Klossowski, Bellmer: Three Approaches to the Flesh.” Art International. October, 1973: 23-28, 65. Print.

Webb, Peter. The Erotic Arts. London: Secker & Warburg, 1975. Print.

Webb, Peter with Robert Short. Death, Desire and the Doll: The Life and Art of Hans Bellmer. Los Angeles, CA: Solar Books, 2006. Print.

Jeremy Bell is currently finishing his PhD dissertation on eroticism and cruelty in 20th century modernism in Cultural Studies at Trent University. Bell takes an interdisciplinary approach to the antinomies between community and intimacy, between art and theory. By placing them in conversation with one another, he looks at the development of a European cultural and social avant-garde.